|

|

|

Evidence Suggests Price Does Not Always Equal Quality

Posted by Mike P. on 2017-01-04 10:13:34

(9901 views)

|

[News] |

When it comes to wine, for some, the price tells them that a wine is good. But after crunching the numbers and analyizing trends, is this really the case? An investigative journalist looks into the weird world of wine.. When it comes to wine, for some, the price tells them that a wine is good. But after crunching the numbers and analyizing trends, is this really the case? An investigative journalist looks into the weird world of wine.. |

|

William Koch — yes, one of those Kochs — is giving a tour of his wine cellar when he asks the obvious question: “Did you see the wine bathroom?” he asked. “Wanna see it?”

It’s an opulent cellar, replete with Roman mosaics, a Guastavino-style ceiling and a Dionysian bust. The bathroom is, one can’t help but assume, where Koch and his guests unzip the flies of tailored Brioni suit pants and catch final glimpses of $1,000 bottles of Burgundy and Bordeaux, since metabolized and micturated.

But some of Koch’s bottles will now meet different ends. Koch gave a tour of the wine bathroom for a promotional video ahead of the sale of more than 20,000 bottles from his cellar, at Sotheby’s, in New York. The sale, which took place over three days last month, fetched $21.9 million, going down as one of the richest wine auctions in history.

I watched the sale’s final day unfold, fascinated — and a little dismayed — by the wines fetching these handsome sums, where they came from, and where they were going. Questions like that are sparks a FiveThirtyEight writer is obligated to kindle.

Off I went in search of data, and I found it in the form of a juicy, dense spreadsheet containing 140,000 wines from 10,000 producers in 33 countries, and their prices. The data was sent to me by Peter Krimmel, the CTO of Vinfolio, a fine wine retailer. It’s wide-ranging, assembled by the company using auction results from 12 major houses, including Sotheby’s, representing “the vast majority of the fine wine auction market.” For the 140,000 wines covered, it has data on the producer, year (the wine’s vintage), bottle size, region, subregion, American Viticultural Area (where applicable), color (red, white or rosé) and price.

After quaffing the data, what I found was a high-end wine market, and a blockbuster auction, with notes of geography, chemistry, economics, culture and thousands of years of history — with a detectable aroma of bullshit. Let’s have a taste.

“Starting in Bordeaux, with the Latour,” auctioneer Jamie Ritchie said, as he opened the Koch sale’s third and final day. Bids flew in via the telephone, the Sotheby’s website, and the floor of the auction room on New York’s Upper East Side. It was a good place to start the day — no place gives a better introduction to the history, and economics, of wine than France.

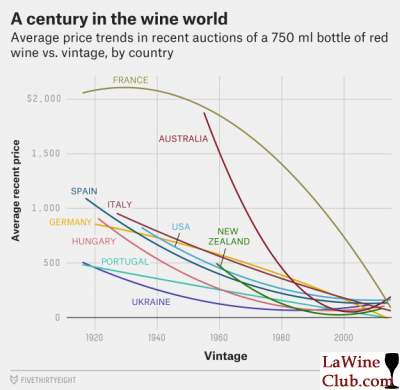

Château Latour, in Pauillac in southwestern France, traces its history back to 1331. It was a favorite of Thomas Jefferson’s. Koch had set out to collect a thorough “vertical” of the wine — owning at least one bottle of Latour from each of the past 100 years. Today, Latour sits at or near the apex of the some 7,000 producers in France’s Bordeaux wine region. It’s a storied region; the Romans were the first to cultivate vineyards there. Millennia later, it’s a useful place to show what almost any wine drinker knows: The older stuff is the pricey stuff.1

In Bordeaux, as almost anywhere else in the world of fine wine, wines get more expensive as they get older, and that effect accelerates the older the wine becomes.2 There’s a lot going on here — aging and its complex chemistry, market scarcity (people do sometimes drink the wine, after all), vintages perceived as particularly desirable or undesirable as a result of the weather, the scope of the data set.

The increasing value of older wines is an essentially universal phenomenon in the high-end auction market. But for the rich oenophile, old wines may not be such a bad deal. “Although old wines are expensive, I think they’re actually priced more reasonably than new wines,” Robin Goldstein, editor of “The Wine Trials,” told me in an email. “Old wines’ value is driven by their age-worthiness and verifiable storage history, which really does impact their taste, whereas new wines’ value is driven by critics’ rating scores and hyper-inflation in the high end of the market, neither of which correlates with taste.”

Leah Hammer, Vinfolio’s director of cellar acquisitions, echoed this idea. She told me that one reason older wine is expensive is because it was too good to drink right away. So, say 1960 was a bad year for Bordeaux wine because of weather. The bottles from that year would tend to get drunk right away, as the Bordeaux faithful consumed the swill they didn’t think was worth keeping. The best stuff — from 1961, say — was saved for later. Two effects — the aging of the wine and the selection of the good vintages — drive the price increase in the chart above.

The most expensive Bordeaux wine, on average, and one of the most expensive wines in the world, comes from a tiny little place called Château Le Pin. (Two double magnums of 1995 Le Pin were sold for a total of $30,000 at the Koch sale.) It sits on less than seven acres (less than four soccer fields) on Bordeaux’s Right Bank and produces just 5,000 to 6,000 bottles a year. A single bottle averages over $2,000. One other Right Bank producer, Petrus, a 12-minute drive from Le Pin, also cracks the four-figure average. (For those of us who can’t afford a bottle and would like to taste vicariously: Robert Parker, the influential wine critic, found flavors of lead pencil, roasted nuts, smoke, spice, fruitcake, black cherries, white chocolate, cola, kirsch and black raspberry in the 1995 Le Pin.) |

Details |

|

|

|